On Reading Great Literature – 1

DISCLAIMER: If this writing at all gives the impression, even the most fleeting one, that I am stating myself to be a well-read person of Western literature, then please accept that this is not my intention in the least. Yes, in my life I have read a little, perhaps a little more than the typical individual sharing my general social and educational background, but then again, as any habitual reader of literature will readily admit, I have not read anywhere as near to what I should have read by this age, or at least, not anywhere near to as much as l would have liked to have read by this age in life. For the more you read, the more you realize, with some forlornness if I may put it as such, that time is running out and there is so much that is still to be read – which in truth should have been read a long time ago.

On with the writing then …..

William Clark Styron Jr. was an American novelist and essayist who won major literary awards. Perhaps his most famous novel, made into a film of the same name, was Sophie’s Choice. One definition of a great novel, according to Styron (and I simply loved this) is that ‘a good book should leave you with many experiences, and slightly exhausted at the end. You live several lives while reading it.’

Isn’t that wonderfully stated? I would go on to say that reading great literature is always a moving experience, evoking profound emotions, and often, conflicting ones. It goes well beyond giving the deep pleasure of reading language well-written, incomparable as even this is. Great literature completely immerses you into the story itself, a part of which you become as you read on, even at times subconsciously identifying yourself as one of the characters. You may find yourself empathizing with the protagonist or with another character, even as you develop ire with another. As the story unfolds, you feel joy and angst at different times, at times fear and trepidation, and at still other times, relief and contentment – all in one great novel!

Get addicted to reading and soon you will hardly ever turn your television on, or feel the need to unnecessarily socialize for fear of ‘missing out’. Small talk will begin to bore you with its meaninglessness, and every single day you will yearn for that hour or two when you are alone once again with the book you are currently reading, shutting out the outside world almost with a sense of freedom and relief! I am by no means implying here that the reading habit makes you a loner or unsocial. But perhaps you do become more selective of the company you seek, gregarious as the human being intrinsically is. And yes, your principal pleasure in life becomes reading. And what a pleasure it is indeed!

Personally I read fiction mostly. The non-fiction that I do read occasionally is on topics like travel, history, philosophy, and nature and wildlife. I stay far away from self-help books – the 7 or 9 or 11 habits (have you ever noticed how such magical solutions to make you immensely successful in life invariably espouse an odd number of steps to be followed?). At times I read biographies or autobiographies of true visionaries, but avoid autobiographies of politicians and retired senior government or military officials, for I find these to be biased, superficial , egotistical, and not telling what really should be told of their life’s experiences. I suppose all these types know too much of the behind-the-scenes skullduggery to be able to tell the real or the whole truth, without inextricably compromising themselves too.

In fiction itself, I am definitely not one for the occult or the supernatural; nor for science fiction or fantasy or horror. I am sure there must be some great books out there on these subjects too, but somehow these have never really appealed to me. Exceptions are there of course. For instance who can deny the awe of Bram Stoker’s Dracula?

The fiction, contemporary or classic, which draws me to it like a candle draws a moth towards itself, has one principal feature – the exploration of the human mind and the human soul, and how this shapes interaction of individuals and their relationships, as the author ingeniously weaves the fabric of a deeply absorbing story, leaving us, the readers, ‘slightly exhausted’ as Styron had advocated. Such fiction is fascinating to read. It’s thought-provoking and insightful, and at times even disturbing. But almost always it is spiritually uplifting and soul-satisfying. A single great work of fiction gives you a level of understanding of the complex creature that man is, which a whole library of ‘how to’ books cannot even come anywhere near to providing.

A young colleague at work, convinced by my extolling of great fiction, asked me once what all should he get into reading? I remember groaning inwardly at this innocent question, which early enough in our conversation I should have realized as inevitable to be posed. I parried by questioning him back as to what all he had read so far in his life. He named 2 or 3 fast-fiction best-seller authors whose works usually adorn the front-facing stands of airport lounge bookshops. I cringed and asked what else?

‘The Alchemist,’ he proudly replied. I nodded encouragingly, not surprised, for The Alchemist seems to have become the ‘must-read’ great work of fiction of all millennials. Perhaps its brevity is an encouragement for a generation which is more comfortable with communicating in messaging limited to 140 characters.

There was a long pause as I waited in hope for him to name some other books of any worth that he had read. But no more names were forthcoming and I sighed silently, for the ball was back in my court and he now expected me to advise him which authors or books he should start reading.

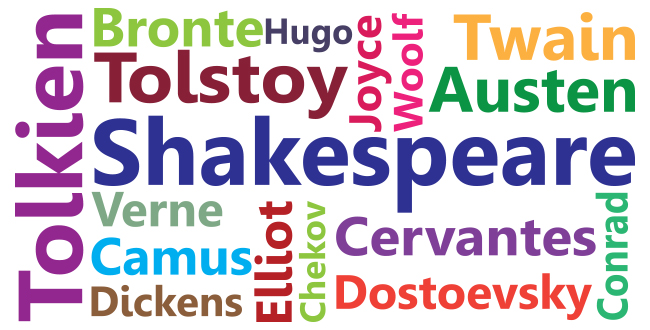

Two score or more names of literary giants from 2 centuries or thereabouts flooded my mind in no particular order – Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekov, Hugo, Twain, Dickens, Steinbeck, Buck, Joyce, Austen, Bronte, Camus, Hemingway, Woolf, Elliot, Fitzgerald, Conrad, Maugham, Kundera, Kafka, Marquez, Naipaul, Pamuk, Shafak ….. and hovering above all these names of gods and goddesses of literature, like the Sun hovers all the planets and asteroids in our solar system, was the name of arguably the greatest literary mind in the past 5 centuries – the Bard of Avon, William Shakespeare, who must surely have been a source of great inspiration in one way or another to virtually all authors, past and present, who are considered to be great since Shakespeare.

I had to make a conscious effort to stop the train of names of still other great authors from making a late entry into my mind. I didn’t want to scare him off just when he was wont to start getting into the reading habit, by rattling off a long list of author names that would simply bewilder and intimidate him. My mind struggled in trying to decide which just a couple of books to recommend to him to read to start with. Can you blame me? Was this not next to an impossible task? How can you possibly recommend just one or two great writers over many, many others? On what basis can one possibly decide?

Consider books which would be relatively easier for him to read and absorb, my mind suggested. Consider great works of fiction the plots or situations of which he could more easily relate to, a supplementary thought recommended.

‘There is a lot of great fiction that has been written all over the world over the centuries,’ I began tentatively, ‘so it’s not easy really to tell you what to start off with.’

He said nothing but looked at me expectantly, waiting for me to go on.

‘What are your interests?’ I ventured to ask, hoping to find a lead in his reply.

‘Sports – mainly cricket, and music and technology,’ he replied almost immediately.

‘What genre of music?’ I dallied.

‘All genres,’ he replied, again promptly, adding, ‘but I am really into Sufi music.’

My heart jumped with joy! What a wonderful opening he had given me!

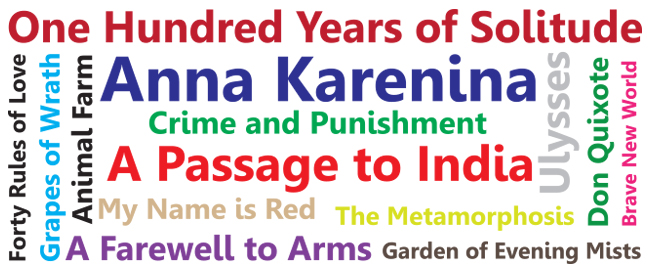

‘Well then you should start off on your reading great fiction mission with a book called Forty Rules of Love, by a female Turkish author of our own times, Elif Shafak,’ I said with a broad smile and a sense of relief.

‘I have heard of it,’ he said, ‘but I am not into soppy romance stories.’

I think my jaw must have dropped then for he looked at me quizzically, observing the shocked expression on my face on hearing what he had said.

Recovering quickly and trying not to sound condescending, I said, ‘Forty Rules of Love is not a boy-meets-girl soppy romantic story,’ I said and paused, and then to make him feel at ease I conceded, ‘even though the title might suggest this.’

He said nothing, feeling that I would go on.

‘It’s about Sufism,’ I explained quietly. ‘It’s set in the times of Moulana Roomi and Shams Tabrez. It’s one of the most fascinating books I have ever read, and if you are into Sufism, I strongly recommend that you start off with this one.’

His eyes lit up with what I concluded were aroused interest and excitement. ‘Forty Rules of Love,’ he intoned, almost to himself, as if indelibly writing the name of Elif Shafak’s masterpiece novel into his memory.

‘Who is the author, you said?’ he queried.

‘Elif Shafak,’ I replied and hastily added, ‘she has written a lot of other books too, but none is as great as Forty Rules of Love. In fact a few are quite disappointing, if I dare say. So don’t read any of her other books before you have read Forty Rules of Love.’

He beamed happily on hearing what I had said, and a sense of relief came over me at being able to zero in on one recommended reading that he could start off with. I felt sure he would be comfortable enough reading Forty Rules of Love to the end, without giving up after only a few pages, totally confused and intimidated, as he certainly would be if for example I had recommended that the first work of fiction he should read to be Kafka’s The Castle!

Then, perhaps emboldened by the breaking of the ice so to speak, I carried on enthusiastically, ‘And if you are really mad about cricket as I am, you must absolutely read a relatively little-known book about cricket, by an equally little-known Sri Lankan author, but an absolute masterpiece nonetheless, called Chinaman, by Shehan Karunatilaka.’.

He rapidly jabbed the names of the book and the author into the Notes folder of his smartphone, asking me to spell the author’s name for him.

‘You know what a Chinaman in cricket is, don’t you?’ I asked a little too desultorily.

A hurt expression came on his face, as if I had asked him how many legal deliveries can there be in an over in cricket.

‘Of course,’ he replied indignantly, and then shot back, ‘don’t you?’

I smiled and gave him a thumbs’ up. He smiled back and the sudden tension dissipated. We were both obviously on the same wicket as far as cricket was concerned!

‘Alright,’ he said, ‘One last question for now.’

I suddenly tensed, the smile leaving my face as a sixth sense warned me that his ‘one last question for now’ was going to somehow corner me. One Last Questions generally tend to do this. And corner me it did!

‘After I have read these 2 books, which is that one book set in modern times I can relate to, which you think I absolutely must read next?’

My jaw dropped again. For a brief but maliciously exciting moment the devilish thought came to me to tell him to read Ulysses or War & Peace or even The Castle as his third book to read. I knew that out of faith in me he would certainly make the attempt to read whichever book I named, even if the effort would reduce him to tears. The temptation to play with him was almost irresistible, justified in my mind by his affront to put me on a spot.

But I couldn’t really give him such a challenge the attempt at which would most definitely make him run away forever from developing a reading habit in general, and reading great literature in particular. I shuddered as the horrible thought came to my mind that he might get convinced so much that reading was a bad idea, that he would never pick up a book again in his life, and turn instead to habitually watching trashy American serials on cable or downloaded in the office, when he was supposed to be working!

No Sir, I decided. It would be quite some time and a lot of reading later when this young man for whom The Alchemist was the sum total of literature read, would be ready to delve into Joyce or Tolstoy or Kafka. But then, which one book, which gem of literature, set in relatively modern times (at his age even the ‘Fifties were like ancient times!) could I possibly recommend to him as the third book he should read after he had read Forty Rules of Love and Chinaman?

It has to be Marquez, I finally decided. I reckoned that even if only a fraction of the subtleties of Marquez’s writing prowess succeeded in exciting him, as I was sure it would, then he would be hooked for life to literature!

‘Your third book to read,’ I said authoritatively, and not a little dramatically, totally relishing the moment, ‘will be A Hundred Years of Solitude, by Gabriel Garcia Marquez.’

He feverishly jabbed the name of the author and the name of the book into the memory of his smartphone.

Leave a Reply